Currently, there are only a few people, really, who play the jaw harp on a sophisticated level or organize events for the instrument, reckons jaw harp expert (acting as musician and smith) and didgeridoo master Jonny Cope from London. During a chat with Helen Hahmann from DAN MOI he talks about what has changed for the instrument on the island, what fascinates him the most whilst playing, and what beginners should be looking out for.

In the last 15 years the jaw harp has gained enormous momentum. It is more present in the public as it’s being recognized as a music instrument and developed further. Globally festivals emerged, time and again young musicians appear in the scene, new jaw harp smiths have started to sell high quality instruments, and books are being dedicated to the very subject. In England, the Wright family are seen by many as the experts, when it comes to jaw harps. John Wright was an ambassador and expert for the instrument until his death a few years ago. His brother Michael Wright just recently published a book about jaw harps in Great Britain and Ireland. Jonny Cope has been an active player for the last decade and added another hotspot for jews harps to the island.

“Playing the jaw harp is kind of an addiction for many players. Either you put it away rather swiftly or you get strongly addicted”, even though it is a simple instrument, says Jonny, the vast variety of styles adds to an astonishing complexity of the jaw harp. “An instrument from China is completely different to one from India or Russia. They involve other techniques and sounds. I’ve never been able to head into one direction, and so I started to learn all of them. I travelled a lot and picked up a lot of knowledge from the local people. Sometimes you are sitting for days and are trying to imitate that sound. This approach makes you better in distinguishing how the tones are created – whether by tongue, by throat, by air streams, or by voice. I don’t necessarily intend to copy someone. The point is rather to share techniques and to integrate them into my own play.”

Though Jonny states he virtually loves all styles that can be played with the jaw harp currently he is particularly fond of the Norwegian art of jaw harp playing. The special thing in Norway is controlling the jaw harp to a degree, where melodies can be played. He opens one of his impressive jaw harp cases, where quite different instruments rest in fabric patch pockets, one of them is made by the legendary smith Bjorgulv Straume. He plays the Norwegian melody “Fangjen” on this jaw harp:

Jonny Cope playing the norwegian tune "Fangjen". Recorded at Ancient Trance Festival in Taucha (2016).

"I was 9 when a friend of mine came to school with a jaw harp. Back then, the both of us had no clue what this thing actually was. He wanted to get rid of it. He made me curious and he gave it to me in exchange for a chewing gum. My grandfather knew this was a jaw harp and he showed me how to hold it and how to produce a sound. But I didn’t end up playing for a long time as it was one of those big English jaw harps. The tongue of the jaw harp constantly hit my teeth, and eventually I stopped playing. It dates back to the 1950’s and I still have it.” Many years later, roughly around the year 2000, Jonny Cope listened to jaw harp music on CDs and remembered the little Twang instrument. He dug up the item from his past childhood barter and discovered the diversity of the jaw harp: about its popularity in so many countries and that has such an amazingly diverse sound. “I started out as a didgeridoo player. I’ve always been interested in unusual sounds and techniques. That’s why I learned overtone singing and then the Mongolian Khöömei. Back then, I didn’t have a teacher, so I learned from listening to CDs. On many of the recordings from Tuva and Mongolia there was also jaw harp music and that’s how I re-discovered the instrument."

In another life he would past his time as a music ethnologist, confesses Jonny Cope. His ears would always be drawn to unusual sounds. Even when somebody in his presence would whistle or hum a melody he would carefully listen as a boy. “I’d say I’m a sound researcher. Same as ever, I’m listening to music that friends bring over. Some of them are ethnomusicologists. They bring by old, rare and sometimes even unlabelled recordings. I’m listening to this crazy stuff and then I’m trying to find out what exactly I’m listening to.” Today, Jonny Cope not only mastered the didgeridoo and the jaw harp, but is also proficient in playing diverse flutes.

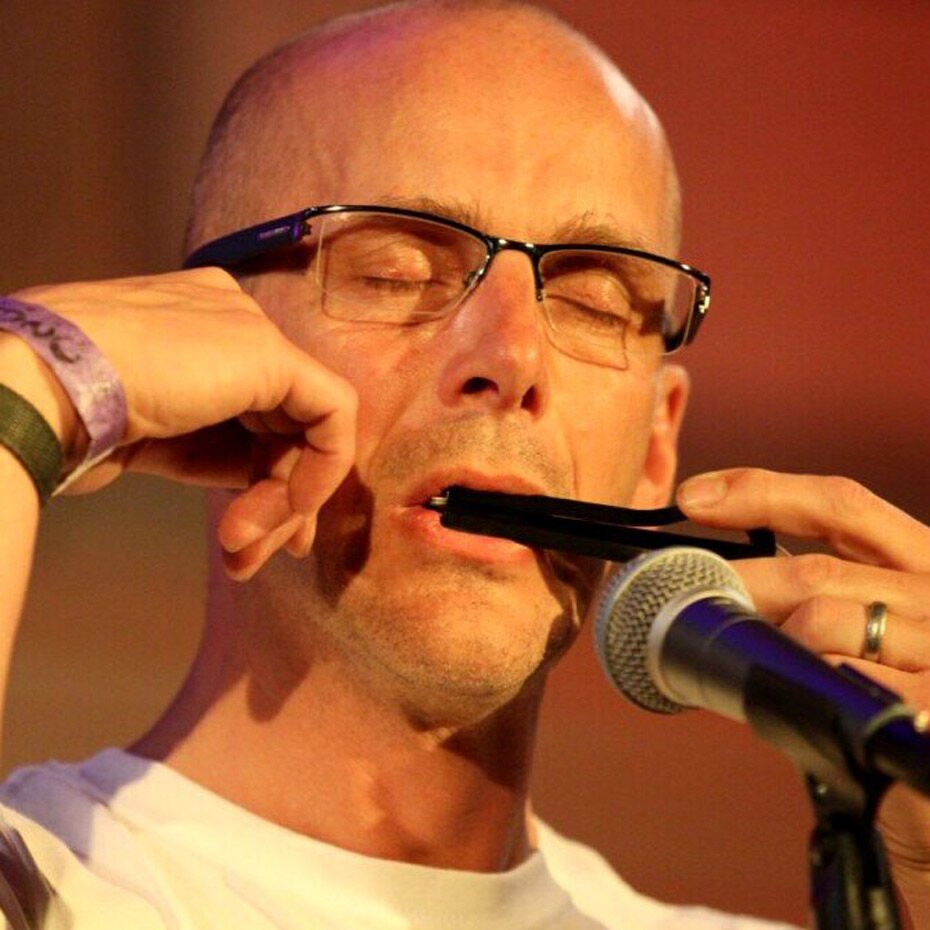

Jonathan Cope at the Ancient Trance Festival 2014

When talking about it Jonny Cope often uses the term “jaw harp”. There has always been some uncertainty about the more common term “jews harp”, which has been controversially discussed in the UK. Until today there is no existing explanation why the jaw harp is being called “jews harp” in England as there is no tangible connection to the Jewish population. However, there are several theories how the term might have been changed based on the Chinese whispers principle. “In France they sometimes say ʻjoue trompeʼ, which means “playing the trumpet”. So perhaps, people heard the word joue and understood jew. That’s only one possibility, though. In Scotland the term gewgaw was used over a long time. But even the knowledge about how to correctly pronounce the word has gone lost. Only a couple of years ago I made a trip to the South of the US. I showed someone my jaw harp and he said, “oh yeah, a juice harp”. The way he pronounced the word sounded like “orange juice”. Then I wondered, what that actually has to do with the jaw harp at all. That’s a good example how people try to make sense when they misunderstand terms they hear.”

In the 18th and 19th century Birmingham in England was, along with Molln in Austria, one of the most productive areas for jaw harps in Europe. The instruments from England were mainly shipped to North America, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. In the Birmingham area alone during its peak time there existed roughly 30 families that produced jaw harps. At the end of the 19th century still close to 20 jaw harp producers were still registered. However, manufacturing the jaw harp became less and less profitable, which led the last jaw harp smith Sid Philip in 1975 to sell his business to a US company. Since then Jonny Cope is the first who started making jaw harps again. “I’m learning to forge the jaw harp in Norway. They forge the Munnharpe – instruments that are slightly different to the English jaw harps. But I like the Munnharpe and am learning the basics there, anyway. I’m already able to produce it in England myself. One of my friends also started to learn the forging business now, too.” Jonny Cope does not only make jaw harps in his forge. As a lover of ancient history he also forges spearheads and swords.

“If you really want to learn playing the jaw harp, I think the most important thing is possessing a really good jaw harp.” Jonny knows what he’s talking about. Having conducted countless workshops he got numerous people acquainted with the instrument. On the online platform Udemy you can even find one of his jaw harp beginner’s courses. “There are simply too many instruments out there with bad sound quality. They are ok to play a simple rhythm. However, who’s able to clearly decipher the overtone sounds and is in to experimenting with sound spectrums should get himself an instrument that actually can do that. Currently, I’m playing with instruments from Estonia, which over there are called Parmupill.” Johnny plays one of his compositions called “Spring” on a Parmupill:

Jonny Cope playing his own composition "Spring". Recorded at Ancient Trance Festival in Taucha (2016).