Producing sound with a jew's harp is easy. One only needs to know the basics - how to take the instrument in one's hand, place it on the mouth, hold it against the teeth and make the reed of the instrument sing. The mystical sound that man can produce with this tiny instrument has captivated many nations for centuries. The earliest jew's harps found in Estonia was a jew's harp dug out from Otepää town hill dating back to the beginning of the 13th century. However, since at that time Otepää town hill was the location of a German fortress, this finding cannot be considered as a proof of jew's harps spreading across Estonia. There are, however, several findings from the 15th and 16th century and it can be suggested that at that time jew's harp was a popular instrument among peasants.

Today jew's harps can probably be found in many households. However, finding people, who can play this instrument, is much more complicated. As mentioned above, it is easy to produce sound with this instrument, but playing songs or melodies takes some practice, as with any other instrument. Seemingly a simple toy, but in practice an ancient instrument requiring subtle playing technique.

Different types and names of jew's harps can be found all over the world: Parmupill in Estonia, Guimbarde in France, Maultrommel in Austria, Vargan in Russia, Munnharpe in Norway, Khomus in Tuva or Jew's harp in England etc. An interesting fact concerning the instrument's English name "jew's harp" is that, in fact, this name does not indicate any connection to the Jews. The name is a consequence of some publishers mixing up a few letters at one point. The initial intention was to name the instrument "jaw's harp" but somehow, when the text was published, "a" was replaced by "e" and since then even scientific publications have consistently been using this inaccurate name.

There is firm evidence that in Estonia the jew's harp was at this one period used for playing dance music. Imagine the whole village dancing after a village musician comes to the swinging square, takes the musical instrument out of his pocket and begins playing a tune. This is not a joke. A village musician played dance tunes - Flat-Foot Waltzes, polkas etc.

Theodor Saar from Kihnu once told that in the 1930s there was a wedding where the only musician was a person playing a jew's harp. As the silent sound of the instrument could not overcome the loud party noise, most of the dancers where looking at and following the rhythm of movement of the musicians foot. This is how they derived the correct rhythm and tempo.

In general there is enough evidence of people dancing to the rhythm of jew's harp to support the story of a man from Jõhvi, who in 1944 said: "... already in the ancient times men used to build big swings... And when they'd had enough of working, they played and sang. Then along came zithers and concertinas, and people danced. Some people carried a jew's harp in their pocket and sometimes its tune was very happily used as dance music.”

Jaan Türk called the jew's harps or harmonicas used in our land frog's harps. The way Jaan Türk handled his frog's harp was completely different from the technique used in coastal Estonia - he did not place the instrument between his lips but in his oral cavity where the vibrating sounds produced something similar to "slurping". His skillful play was very enjoyable.

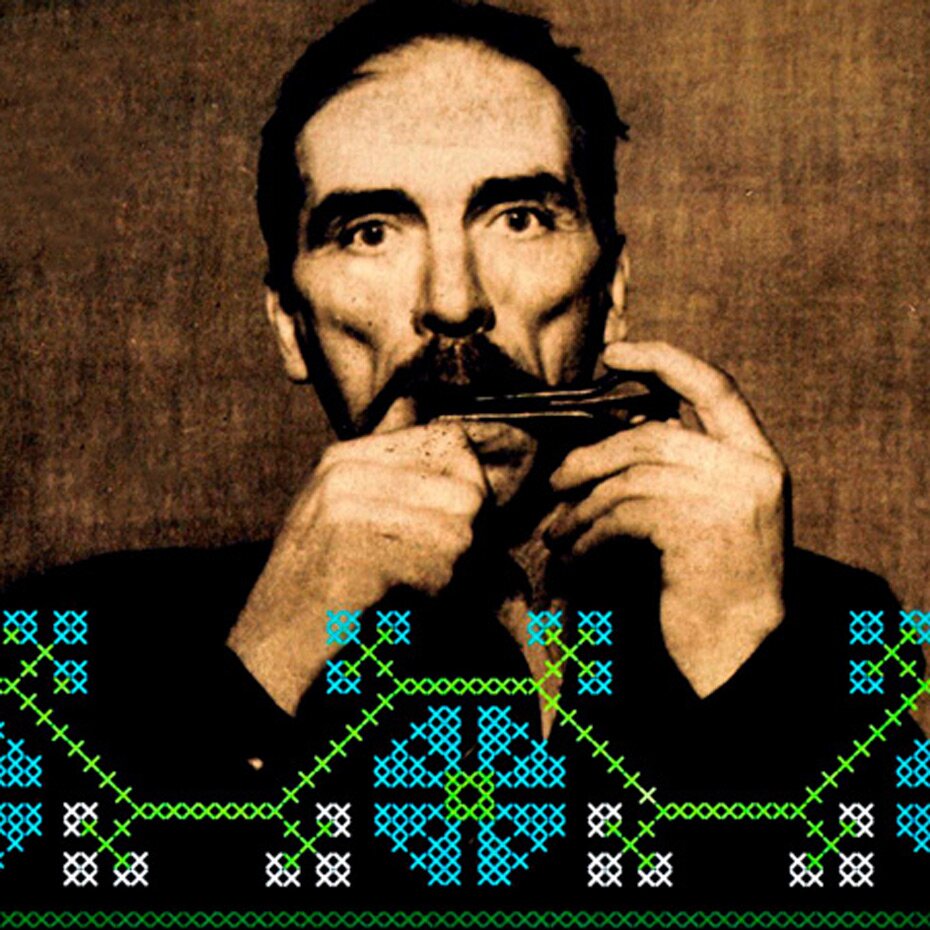

An interesting description of Peeter Vekmann, a passionate jew's harp player: “When Peeter started playing, already his first notes created such silence in the audience that one could have heard a pin drop. The musician was so skillful in using his instrument, and his oral cavity as a resonator, that the sounds he produced were very colorful and versatile. The audience was captivated by his play and did not want to allow him to leave the stage. He had to play again.”

Peeter Piilpärk: a musician played jew's harp, according to their own words, "under the tongue" or "above the tongue". Playing "under the tongue" was the Kihnu way.

Jaan Rand: Jaan, being a passionate musician, always carries his jew's harp with him everywhere he goes.

Ruuben Kesler said: "Whenever I have time to spare from my farm work, I grab my jew's harp because it makes my mind feel happy and my body feel light!”

In his memoirs, August Pulst very colorfully describes his collaboration with Villem Ilumäe, a talented musician: “When I first discovered this musician based on the information received from Lääne-Nigula, I found out he was living in a "smoke hut" (a chimneyless hut with a vent in the roof to let out the smoke) and very soon after that I also saw the musician himself coming around the corner of his hut. When I asked him, if he was the jew's harp player I was looking for, he smiled, placed his hand in his jacket pocket and took out his jew's harp. And I said: ‘Well, look at the true musician - always carrying his instrument in his pocket just as some smokers carry their pipes!’ This statement lit up his eyes and he immediately replied ‘Well, yes, you know I have been playing that instrument for a little while! We call it a mouth harp.’" Then the musician told me that his mouth harp was 58 years old. He had only changed the reed since it breaks after a while.

This post was written by Cätlin Mägi (formerly Jaago) for DAN MOI World Music Instruments. If you are interested in more details on the Estonian jew's harp culture and history we strongly recommend Cätlins excellent book "Eesti Parmupill - Estonian Jew's Harp", available in our webshop.