"I found my first Jew's harp in the street. I picked it up and first of all had to look up on the internet what small strange object I was holding in my hand. I found out that the Jew's harp exists in Bali, in Vietnam, in Austria and in Sicily - that really impressed me, such a small instrument that can be found all over the world, an old instrument that entire festivals are dedicated to ... from then on I knew that I absolutely wanted to meet people who played the Jew's harp."

The Canadian ethnomusicologist Deirdre Morgan became fascinated by the Jew's harp ten years ago and has been captivated by it ever since. When Deirdre got to know the Jew's harp, she also began to discover Gamelan music and started playing with a Gamelan group at Vancouver University. "I fell in love with Balinese music and with the Jew's harp at the same time. It was therefore only logical that I was interested in the Genggong, the Balinese Jew's harp". In 2008 Deirdre Morgan did her thesis on the Genggong at the University of Vancouver in British Columbia. The thesis can be found online as an Open Source document under the title "Organs and bodies: the Jew's harp and the anthropology of musical instruments".

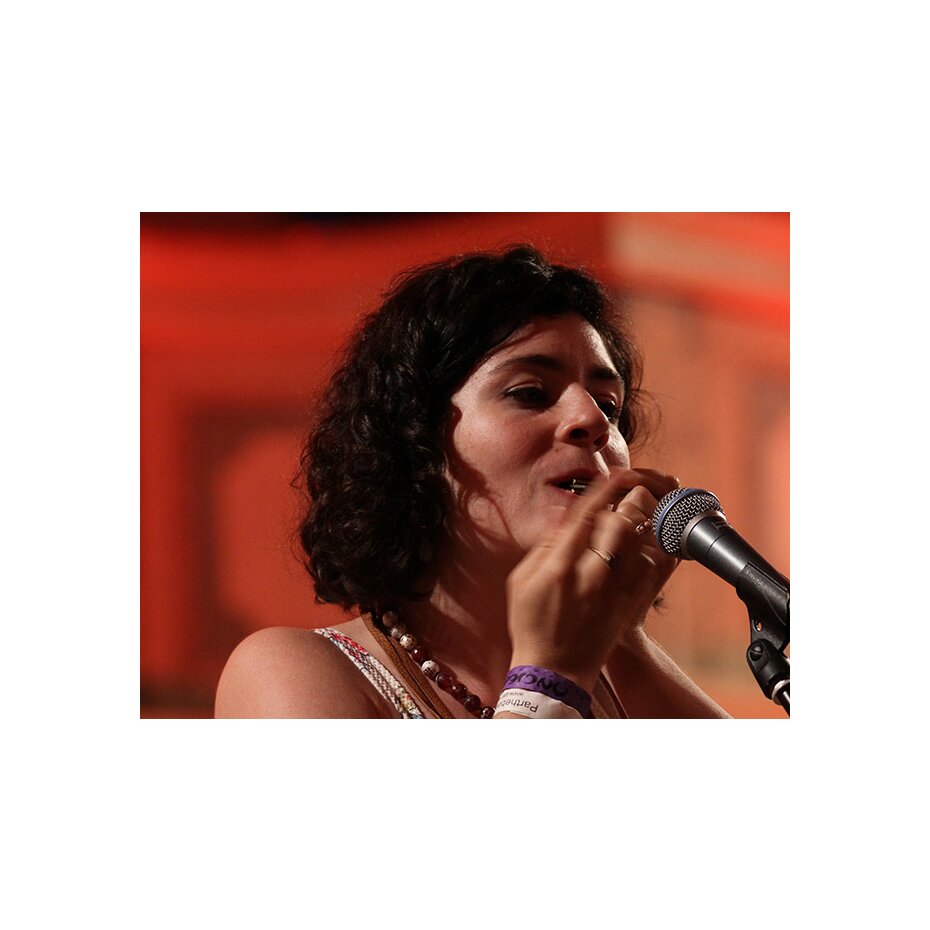

Deirdre Morgan and Aksenty Beskrovny: Touchtone Duo

In the meantime Deirdre does not only investigate Jew's harps but also has become a Jew´s harp player on stage. As a soloist or with Aksenty Beskrovny as "Touchtone Duo". "The Jew's harp sounds very organic. This sound has depth, it comes from deep within the human body. At the same time the Jew's harp can sound like a robot, like a machine, an alien, something extra-terrestrial, something that is not of this world. The Jew's harp then incorporates both elements, the human and the superhuman." This tonal polarity of the Jew's harp can also be found in the social function of some Jew's harps: "The Jew's harp is connected to shamanism and spirituality. There are also traditions, in which the Jew's harp serves as tool to establish contact with people in this world or in another world. The working title of my dissertation is: 'Speaking in Tongues', meaning the incomprehensible speaking during prayer. 'Tongues' in English also refers to languages, it can therefore also mean speaking in different or strange languages. For me every style of Jew's harp playing is a new version, a new language. Last but not least, the English 'tongue' is also the name of the metal spring of the Jew's harp."

In her dissertation Deirdre Morgan explores the question, why people play the Jew's harp and what the sound of the Jew's harp means to them. Her research is firmly anchored to the presence, she does not write the history of the Jew's harp, history is only considered to explain current developments in the Jew's harp community: "For instance I am interested in how such a strong Munnharp community can exist in Norway and has already been maintained for years. So I head off and have numerous conversations with Jew's harp players and smiths and naturally also with the key figures in the scene, those who organize festivals, workshops and concerts." One can ascertain that for many in the community the driving factor is to have a very special knowledge that only few people possess, they are convinced to be preserving a tradition. Deirdre Morgan returns again to Norway: "the traditional melodies there are in no danger of being forgotten. There are so many people who know the instrument and play it. In Austria and Sicily playing the Jew's harp is undergoing a revival because people are looking for something unique they can identify with. While doing so, people from many different perspectives draw closer to a tradition; there are those who tend to be conservative who cling on to an allegedly historically handed down understanding, and there are the experimental currents which are driven by the need to integrate the instrument in a modern context."

As a board member of the International Jew´s Harp Society (IJHS), Deirdre Morgan reflects on the IJHS congress in 2011 in Yakutsk and considers it a milestone for the music of the Jew's harp. Since then, there has been a palpable upturn in the international Jew's harp scene, she recounts. Within a few weeks, new Facebook and Twitter groups sprang up which allowed people interested in current events in the community to keep up to date. Yakutsk was an extraordinary experience for many participants. The younger generation of Jew's harp players met up there for the first time. After that people began to network, to communicate via online portals and to exchange material and information. This way the community has become much more visible and present.

The Jew's harp hides many stories that until now have not been discovered or told - whether about the arrival of the instruments in the "New World" on emigrant ships, the practice of music by indigenous communities in South America or contemporary trends in Indonesia. "What I wish" says Deirdre, "is that people visit museums and archives more frequently, in order to discover old sound recordings of cultures, to listen to them and then see if they can produce these sounds themselves and further develop them. These sources are often so rich that they can help to bring less vivid or even forgotten traditions back to life. In Norway and Estonia, this approach has already been very successful." All in all, it would be desirable that people one again show more interest in their local traditions.